Kobayashi's Ghosts

Almost ten years ago, Masaki Kobayashi died. I would like to pay an homage to him. That Shomingekihas always received my contributions, and that I opened my participation with an interview about the japanese director explains why I thought fit to celebrate Rüdiger Tomczak's dedication for ten years to this magazine by proposing this trip back to Kwaidan.

*

Shots, amalgams of shots, traveling pursued from one scene to the next. Tales. Tensions. Contradictions felt as exemplary of a feeling of justice; indifference, as one of power. Whole films as favorite: Kaseki, Seppuku,Joi-uchi, Ningen no Jôken. Moving memories of others: Nihon no Seishun 's officer's arrogance and brutality, the hero's timidity, the meeting with the former lover and the coming back to the spouse; Kuroi Kawa's light on Tatsuya Nakadai; the surrealist nightmares in Kabé Atsuki Heya, the grin of the baseball player in the final close-up of Anata Kaimasu; revelations of the Japanese's armies'atrocities paralleling the indifference and blindness to their own behavior in colonies of the Allies, during the three year Tokyo Trial, as shown in the director's sole documentary of the same title. All these come to mind, while I think of the steady pace, white capped (except at our last meeting, when he wore a golf one) man who, instantly, from 1972 to 1994, at each of our meetings at the Saeracoffee shop, close to his downtown haven of the Hayuza and his producer Hara's office, plunged in the evocation, not of former films, but of the one in process: in the end, he made allusions to his dream of shooting a documentary about the temples around Nara, thus fulfiling his youth love for repositories of places echoing the japanese connection with the silk road, the interrelation of buddhism and art, from which Kwaidantakes its depth. Always a few words also about his more than twenty tears' project of adapting Inoue Yasushi's novel, Tonko, which dealed with a now vanished city along the silk road. He wanted the novelist to see the adaptation, and another producer had the chinese contact: Sato Junya was hired and it pained me to see what the novel became. So now still I imagine from Kobayashi's script, that added the rediscovery of the Tung-Huang grottos as introduction, what the film would have been. Really for me, this is a ghost film...

Would Kobayashi find it ironic that besides sometimes Seppukuand Ningen no Jôken, Kwaidan should be is most often commented work, and that it sould be so not by <<auteur>>'s films buffs, but by genre, if not horror films fans? I often hear filmmakers or cinephiles pay their dues to Kurosawa, while describing a Kobayashi's jidai-geki... No young Japanese below thirty that I randomly meet knows his name or even his films.

As the sketch <<Mimi-nashi-Hoichi>> is my favorite as well as the one I most frequently taught from, it seemed appropriate that this homage should take it as its starting point.

1964

When Kobayashi produced and directed this film, he was an acclaimed director, honoured by the Cannes Grand Prix for Seppuku( an honor to be reciprocated with Kwaidan). His stature among Québec filmmakers and cinephiles had been kindled by a surprise midnight showing of Ningen no Jôken. If Karami-ai(The inheritance) was coolly received, Seppukudivided critics: tenants of Nouvelle vague or marxist ideology pointed to its academism, others to its solid composition matching the trial made of the way those in powers exploit high principles to their own ends, as well as how History should be questioned, since the victor's tale can be biased.

From an evocation of the Manchourian war(Kobayashi knew by experience, as well as the POW's condition) to the theme of inheritance when reduced solely to its money aspect to that of the transmission of History, Kobayashi, even though soliciting the past, was addressing his contemporaries. He felt shocked about their obsession with economical reconstruction and desire of amnesia. Not so much, as is wrongly believed by other wise better informed foreigners, that Japanese did not hear about their armies'atrocities, war sufferings, the Hiroshima experience, China's invasion: in novels, Fumio Niwa, Masuji Ibuse, Shohei Ooka, in films Satsuo Yamamoto, Kaneto Shindo, Tadashi Imai, among others, maintained the literary and films testimonies and questioning that would endure up to now; in the 1960's, Toho would each August illustrate Japan's tragedy and grandeur, but this steady nourishment of nationalistic feelings was matched by other more critical films. Still, in 1984, Kobayashi's own Tokyo Trial, displeased, especially with the Nankin episode, Japanese right wingers and left shaken former westerners POWs in japanese camps.

But in 1964, Kobayashi felt, as he always will afterwards, that his predecessors works and his own Kabe Atsuki Heya and Kuroi kawawere not sufficient to end the necessary expression of the need to stay aware of our priorities: once passed the screening, the spectator 's emotions did'nt seem to influence his outlook on life enough to help define politics and economics. Did he had in mind his friend's Kobo Abe's:<< As we think of time, we act?>>

If those films evoking the war experiences echoed in so many Quebeckers cinephiles of a country who did 'nt fought battle since 1837 on its own ground, it is because we were at the brink of a revolution we termed quiet, even though it carried away religious and classical references in education very rapidly, considering a century of strong dominance. Many of us were pondering what to keep and what to change within our tradition, believing it had some resources to help us adapt, even orient the ungoing change. Those of this mind discovered a kin spirit in Kobayshi's endeavour to appeal for a critical approach of tradition.

Kwaidanwas made, according to Kobayashi, to testify to the complexity of tradition, how it should not be reduced to how it failed, to what was upheld by the militarists, how it was rich with spiritual resources still significant for our times, as it could instill in us a clearer acceptation of the complexities of our needs: this, in opposition to the sole desire to be the best, the dominant... Thus History at the time of film production mingles with History as frame for the tale the film narrates. And Kwaidansolicits the resources of art, religion, history to shed light on human being's necessary quest for meaning.

The sketches

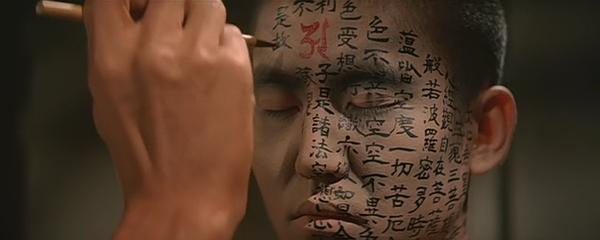

In the longer version, Mimi-nashi-Hoichi comes in third place, after two sketches devoted to the relationship between men's idealization of women's role and the reality of the latters' agressiveness as well as men's fear of the unknown powers lurking within wives and lovers... Both sketches underline the cultural, rather than natural definition of stereotypes, as kindness, compassion, forgiveness are clearly decided, when so, by the women, not reflexes. But the first story also deals with ambition as destroyer of a sounder basis to our life, that is complicity, not protection or advancement. By opening thus, Kobayashi sets the tone for Kwaidan: it is about priorities, illusory values, ghostly ones... The women in the third sketch are, like men, resolute not to fall in the hands of the Genji enemies. Here the tale focuses on the relationship between the artist narrating, as a profession, the Tale of Heike, from the point of view of the defeated clan, and the ghosts of the wandering warriors, left floating at sea without burial... That art is not only technical skills, but foremost moving when rooted in the artist's experience of suffering and incapacity to express himself at the time he was in the midst of it, is thus illustrated by this mix of Lafcadio Hearn's two different stories: the mix in itself is expressive of the director's wish to inspire a meditation on the significance of tradition.

The last story has been puzzling for certains viewers, for it deals with a malediction: those who try to complete a certain ghost story die before conclusion. If artist have to transfigure their own experience, they are in danger of being obsessed by their project, so much as to never being able to REALize it, so that they only DREAM it... Kobayashi, so intent in telling of his current projects, so taken buy his lifelong dream of adapting Tonko, thus appears to me closer than it seems to the core of this tale. But his attention to my needs and comfort, and hence his capacity to distance himself from his endeavour, were an indication that, while even in the passionate rendition of his planned film, he was not taken by it, contrary to the writers and readers of the fatal tale...

One character inside a well seems to tell us farewell, according to westerners' sign langage. Actually, in Japan, the hand movement is an invitation to join him... amongst the ghosts, always a permanent temptation...

Arts

As Mimi -nashi-Hoichiappears in continuity with other tales, so do many arts interplay within the sketch.

Toru Takemitsu, for Kwaidan, mixed japanese instuments and musical modes with western ones. As well he included concrete music. The film overall score is thus multilayered, in echo to the director's preoccupation with the meanings of tradition. The third sketch stresses biwa(variety of lute) and voice so intimately united by learned japanese, that hearing one is thinking of the other, and ressuscite memories of The Tale of Heike, to which they are linked as its first and foremost mean of transmission.

This tale, popularized in the second half of the 20 th century by the novelist Eiji Yoshikawa, more famous in the West for his version of Musashi Miyamoto's saga, narrates the conflict between the Heike and the Genji. The film focuses on the episode of the battle of Dan-no-ura, from the defeated Heiké's standpoint. Thus echoing Japan's defeat in 1945, and touching a cord with Quebeckers emblematic battle of the Abraham plains. The defeated are united in a knowledge escaping the victors and confronted with the necessity to question the representation of themselves.

Although some heroes stand up, the whole clan becomes a character. The epic, in turn, nurished with themes and motifs Nô, Kabuki, novels, as well as paintings: the sketch brings back literary echoes, up even , amongst foreigners, to the Iliad.

As far as paintings are concerned, they are, as biwa is musically, picturally intertwine within the narration. Vertical and lateral pans and travellings( pursued from one scene to the other, like if in a continued movement) frame rolls(emakimono) already conceived to be seen almost in movement, since they had to be rolled from right to left; they also tended to adopt an oblique angle on their subject matters, relayed here by live action shots. Moving clouds and smoke echo the stylized ones emakimono are famous for. Thus the modern medium is used with what are its specifics tools, light and movement, in order to recapture the spirit of the older mediums. Tradition inspired modernity. But tradition is not limited to Japanese materials. For Japan, even though an island, and liking to insist on it, has a long story of curiosity of things coming from abroad. From their youth, 20th century artists are immerged in western music as well as paintings: it has become their tradition. Thus the drawings of flame on the sky are not only an imitation of an emakimono's one, but an assimilation of surrealist imagery's pertinence. This is not new in Kobayashi, as Kabe Atsuki Heya, reminds us. And when the director evoked the surrealist, the first name that came to his mind was Max Ernst, of whose touch one can find a clearer sign in Yukionna'sfrozen sky. With the art director, Kobayashi, the former art historian, painted himself the set's background...

In 1994, when I last met him, he ravished over the quality of the DVD version of Kwaidan in its rendition of frame and color and delineation, feeling a second life was given his film. Being open to tradition does not contradict looking for the best in modern visual techniques...

The movements and pauses of actors, the richness of colors in costumes, as well as the burlesque episods with the temple helpers, echo a Kabuki rendition on Nô theme, including, as oppose to the latter, an open acceptance of theatrality and artificiality as a mean to provoke an analog of the real emotions of the characters involved in the story. I am reminded that this use of set gave place to one of those coincidences,<<given by the gods>>, that the director liked to evoke vith glee. No studio were vast enough to rebuilt temple and nature as wished, and, with a desperate search from helicopter, Kobayashi found former army barracks... So this evocation of pains of war on the Inland Sea was reconstructed in a place once bustling with soldiers... Ghosts again...

Time

Fiction is reconstruction, and when so strikingly manifested, becomes a clear indication to viewers that it is not THE past that is represented, since IT flows. What is berore our eyes is reconstruction, that is an interpretation. Upon looking on ancient works of arts, the range of our curiosity about our own complexity will open us to read with passion what our predecessors have focussed on, given form to and kept silent about: are these preoccupations and points of view still valid? Thus, setting a tale in the past is not so much inviting us to travel to it, but to explore our present from an alternative angle, an ...oblique one.

Furthermore, our images of the Past as well as of the Present and of our Identity are mirrored by the overlaps of influences and mediums this sketch proposes. Memories crosses path with sensations, the film, at each viewing, enters the fabric of our memory. Art gives form to our complex desires: to stop time, re-live it, get relieved from it!

Time and its impacts are at the core of Hoichi's tale. As a tale it is made up of choice, elongation, shortening of episodes as well as syllables and music notes. Time is present trough flowers and melon, iconized as eternity with the pine motif. Night induces visions, day clarification. Studio filming itself prevents the submission to weather, enables to fix the clouds... Superimposition gives concrete form to simultaneity - and the ambiguous nature of ghost, here and not here, as any cinematic figures who in 2-D eludes its 3-D source... Filters, angle, camera movements, black screen, all play with the characters interractions with time, as well as ours as viewers. Desires of omnipresence and omniscience are thus fictionalized in an effort to attest of our sense of time both as sequel of instants and as eternity lurking behind our feeling of transiency. Editing adds to these the play between shots that propell action and those that describe; repetition

alludes to emotional cycle, but narration proceeds, irreversibly: ghosts, half-living, half-dead, linger in between... While the projection of the film follows the law of irreversibility, memories stay , like after-images. Fantomatic images...

Conclusion

Kobayashi, many times in our meetings and in interviews with critics, paid tribute to his <<master>> Keisuke Kinoshita, as well as Sadao Yamanaka. Assistant to Kinoshita, he could witness a master experimenter in film resources, ready to try new means with each project. More consistent stylistically, he could see, once himself a director, his mentor's energy in using traditional arts to enhance his rendition of the Shichiro Fukazawa's novel Narayama Bushiko. In turn, not only the frequently mentioned Milius and Coppola refered to Kwaidan, but also chinese directors of ghost stories and even Fernand Dansereau in his rendition of the clash between missionaries and american Indian, in Le festin des morts.

However, despite the foreign critical reception of the film, its distribution in many countries did not enrich the director. After having fought censorship within Shochiku( Kabé atsuki Heya, a few seconds shot of Kaji and his wife in Ningen no Jôken), after even fighting up to the court for his director's right, Kobayashi, now an independant, had to coproduce his following films, and for Kwaidan, hypothecate his house. Each following films was thus the result of a fight for funds as well as the power to give his work the scope he desired. This determination I have witnessed being admired by directors different in style or philosophy. So I could understand his own pleasure in accounting how <<the kamis>> brought snow on cherry flowers, when, at the morning of shooting, flowers already in bloom, he didnt know how he would go about shooting the desired scene for Kaseki. Or, the one were a young man is requested to commit harakiri with his own bamboo blade(that could not cut a vegetable!, suggest a character): the evening before, Kobayashi, drinking saké, a bit drunk, falls towards the counter, and -eurêka- discovers how the actor should play the movement: by letting himself fall on the blade. So determination does not preclude thrust, confidence in the unknown, the grâce of coïncidence...

Thus 1185, 19 th century, 1945, 1964, all are moments of History meeting in <<Mimi-nashi-Hoichi>>. Arts and experiences from different eras constitute not only the ghosts of the Heike, but of Kobayashi and his contemporaries' memories, as well as that of the film viewers, enriched with the experience of other films and other wars that, lived since 1964, have acted upon our conscience and ability to construct an image of life, of ourself. Even if, for me, this proves more strange upon each of Kaseki's showing - different parts of the film are rediscovered according to my own preoccupations at that age -, revisiting Kwaidanbrings back the ghosts of my encounter with its dirctor, of different screenings and past-selves, of those with whom I was and discussed the episod.

From film to film, always curious of the impact of History on the character's destiny, Kobayashi deeply gave form to my own sense of the ebulliancy of life, forever modifying and eroding the fixed form and answers we forge to deal with our uncertainties and we are tempted to reduce tradition to. Wrongly, reiterates Kobayashi. For traditions are the temporary cristallizations of moments of conscience in time, conscience of the interactions of our own complex and permanent desires, and an appeal to respect this complexity, listen to what traditions can give movement to, within us.

Through Kwaidan and his other hard to find films, we should take for his works, his heritage - our tradition now - the time he invited us to devote to emakimono, biwa music, the Tale of the Heike(and its specific oral way to be narrated), Lafcadio Hearn's tales. Masaki Kobayashi's visions still linger in his works, ghosts that invite us, not to follow them, but, once the detour through History and fiction is done, to plunge into being, in the ever moving present.

Claude R. Blouin

Those who wish to read more about Kobayashi might find interest in Le chemin détourné, HMH, Montréal, 1982. The mentioned novels by Inoue and Fukazawa, as well as some of all the other authors refered to, can be found in french and english translations.

Kommentar schreiben

vietnam travel (Samstag, 05 April 2014 13:10)

congratulations guys, quality information you have given!!!